Book notes: Four Thousand Weeks by Oliver Burkeman

My key takeaways from a 5/5 book about "time management."

The “Radical Incrementalist” approach to work

Radical incrementalism is to be serious about working only for a set amount of time on your projects each day, stopping when time is up, and returning to it the next. It’s incremental because it’s about building your work up over time. It’s radical because it says you shall not work beyond the hours you’ve decided to work on it, which ultimately makes the endeavour sustainble over a much longer period of your life.

This is an antidote to overwork, but more importantly, it is a philosophy that acknowledges the finitude and embedded beauty in each day. I’d pair this approach with what Austin Kleon says about a daily practice: “Seasons change, weeks are completely human-made, but the day has a rhythm. The sun goes up; the sun goes down. I can handle that!”

Originality comes after unoriginality

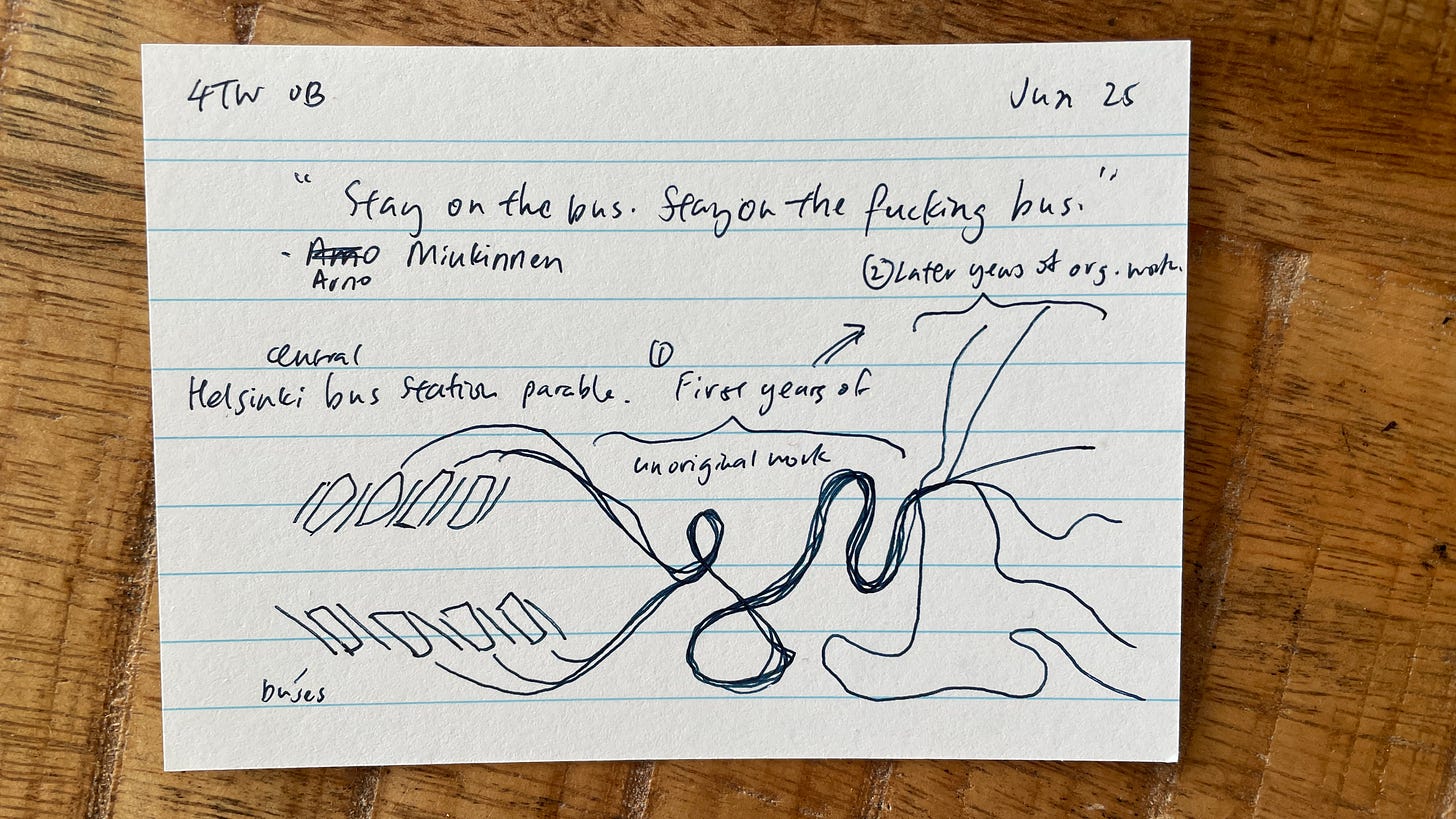

Stay on the bus. Stay on the fucking bus. — Arno Minkinnen

This is the Helsinki central bus station theory. Apparently buses at Helsinki’s central bus station take the same route for a while before diverging.

The point? You’ll likely suck at what you’re trying to do for years before you become good. If you get off the bus and take a different one, all you end up doing is prolonging those years of sucking. Stay on the fucking bus!

On the other side of this is the hobby. A hobby gives you freedom to pursue the futile and enjoy the relevatory freedom to suck at something without caring.

You are paying for distractions with your life

I knew this intuitively but it’s always nice to read someone articulate it:

Your experience of being alive consists of the sum of everything to which you pay attention.

And so when you pay attention to something you don’t especially value (i.e. distractions), you are literally paying with your life.

An important reminder here is that attention is unlike other resources like food and water, which merely facilitate life. Attention just is life.

The Efficiency Trap

The Efficiency Trap is the phenomenon where the more efficient you are at something (say, cleaing your email inbox), the more emails come at you. The more things you work off the conveyor belt, the faster the conveyor belt runs.

This hits home for me as a Singaporean. Singaporeans value efficiency. You already know it if you’ve ever visited the small Asian city-island-country, or if you haven’t been, I recommend going just to feel this. Everything is built around efficiency and nobody realises it’s the cause of so much burnout and dissatisfaction.

A less spoken about aspect of the Efficiency Trap is how technology makes it worse while masquerading as the solution.

The technologies we use to try and ‘get on top of everything’ always fail us, in the end, because they increase the size of everything of which we’re trying to get on top.

Email increased the amount of messages we get in the first place. Facebook increased the number of news events put in front of us. OKCupid increased the number of men/women we notice.

(One of my goals is to build calm tools with technology. I’ll have to bear this in mind.)

The Warren Buffets pilot story — i.e. How to prioritise

Warren Buffett’s pilot asks for advice on prioritising projects in his life. He replies, “write down a list of 25 priorities. The top 5 are what you focus on, and contrary to what you think I might be about to say, I want you to avoid the remaining 20 at all cost.” (I’m paraphrasing Buffett judiciously here.)

Why not just “de-prioritise” the remaining 20? Because it turns out — and I agree — these will be the middling priorities that will tempt you away from the top 5. They will be the things you’ll procrastinate on, even if they may not be easier, because the top 5 are truly what’s most important to you and they will scare you to hide in the 20.

The author recommends we don’t clear the decks. Acknowledge that the deck will be uncleared and that it will leave you a little anxious, but that’s going to liberate you to do the important things in life.

Let go of the limit-defying fantasy of getting everything done. Instead, focus on doing a few things that count.

There are too many big-ish rocks to fit in the jar

The real measure of any time management technique is whether or not it helps you neglect the right things.

Stephen Covey in The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People popularised the parable about a jar with pebbles and rocks. He says you should put the big rocks in first, then sprinkle in the pebbles to occupy the rest of the empty space in the jar. That’s how you get the most of your time.

Oliver Burkeman (author) says no, you’re misleading a whole generation of people by omitting one crucial piece of reality: in most of our lives, the number of big-ish rocks (goals, desires, responsibilities) way outnumber the relatively small sized jar that we’re handed (time). In other words, there will be many rocks we’ll have to choose willingly to not fit into the jar.

The focus therefore should not be how best to pack the jar, but which things to put into and which things to leave out from it. That’s the hard part that we’ll need to figure out to spend our time well.

You can view four thousand weeks as too little to accomplish anything, or you can see it as so much more than if you weren’t born. Flip the script - instead of thinking that you have to do something, start thinking that you GET to do something.

Parkinson’s Law extended (It’s even worse)

One of my favourite “laws” that I quote often is Parkinson’s Law, traceable to the English humourist C. Northcote Parkinson (1955):

Work expands to fill the time available for its completion. — Parkinson

Burkeman makes an important remark in the book. The word “work” here might be too innocuous. It’s really the definition of “what needs doing” that expands to fill the time available.

So if we’re not careful in facing the finitude of our life, we’ll think it’s possible and even desirable to bite off more than we can chew, to attempt to do much more than we have time for.

I’ll always remember the time I submitted my resignation at a job and pitched to management, “I can prepare the documents and do the handovers in 2 weeks. Can we shorten the notice period?”, only to be responded with, “I can’t see how that’s possible. Stay for 4 weeks.” I ended up spreading the work that I could finish in 2 weeks to 4 and left.

On this point, the author has a few sage words: it is vital to confront the painful truth of our limitations, by choosing which balls to let drop, which people to disappoint, which cherished ambition to abandon, which roles to fail at.

Do what you can, don’t do what you can’t. The tyrannical inner voice insisting you must do everything is simply mistaken.

Damn clocks and monks

Why do monks gotta meditate? Just kidding! Though maybe only partially.

Medieval monks needed a way to coordinate waking at a certain time to meditate together, so the story goes, and so they devised a contraption that is the clock.

As they say, the rest is history. Because with the clock, people’s minds began to change. We began to view time as a discrete resource, leaving behind the “task orientation” way of living, which was how medieval farmers before the invention of the clock used to keep time, who orientated their lives according to tasks that needed to be done, like milking the cows when they needed milking.

Once that shift started, we began to feel pressured to use time (the “resource”) well, and if we failed, we berated ourselves for wasting it.

Burkeman cites Heidegger in another part of the book that I think is useful as a resolve here: We don’t have a limited amount of time. We ARE a limited amount of time.